Aren’t pickles fun? They’re such a great way to preserve the harvest, plus making pickles gives you a chance to experiment with flavor combinations. Not to mention, pickles of all kinds make great snacks and accompaniments to meals.

Here we explore two very different ways to turn vegetables into pickles: lacto-fermentation and vinegar pickling (with a hot-water bath to preserve them). We don’t stop with vegetables though, read on to discover some of the unconventional morsels we like to throw in the pickle jar. There are lots of other ways to preserve the harvest, too, including root-cellaring and other non-electric methods.

Learn how to lacto-ferment in our in-person healthy cooking classes.

What is pickling?

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a pickle is “an article of food that has been preserved in brine or in vinegar; specifically : a cucumber that has been so preserved.” The origin of the word pickle is a little murky. In fact, it’s been postulated that it may be the last name of medieval Dutch fisherman who came up with the process. But pickling has been around much longer than that. According to an article from PBS, people were pickling cucumbers in the Tigris Valley in 2030 BC! Wherever there are seasons of bounty and of lean times, human beings have made pickles to help get them through.

Pickling is essentially a form of food preservation that works by creating an environment where spoilage organisms can’t thrive—either because of the acidity of vinegar or the salt content of a brine. That’s what makes it such an effective and versatile method, whether you’re preparing a few jars for the fridge or stocking a root cellar.

What gets pickled?

Vegetables are by no means the only foods that get the pickle treatment. However, cucumber pickles and sauerkraut (lacto-fermented cabbage) may be the most popular. Both limes and green mangos are very common fruit pickles in India. Meat can be pickled too. For example, corned beef, pickled pig’s feet, and herring in wine sauce are examples of this. Even whole, hard-boiled eggs can find themselves floating in brine. Feta is a common kind of cheese that gets pickled in its own tangy whey, plus generous salt.

A few of our favorite unconventional pickle ingredients

- oxeye daisy buds and flowers

- Milkweed pods

- Garlic scapes

- Hemlock tips

- Daylily buds

- Basswood leaves

- Wild mushrooms

Learn More Natural Cooking Techniques!

Join the waitlist and be the first to know when new classes open up for registration!

We’ll let you know when classes open for registration, and send you our fun and informative newsletters.

Lacto-fermentation vs. vinegar pickling

Using vinegar or salty brine are two of the most common ways to pickle.

In the case of salty brine, beneficial bacteria eat the sugars in the vegetables on their way to becoming pickles. As a result, lactic acid is released, turning the saltwater into an acidic solution; this process is called lacto-fermentation. For vinegar pickles, salt is almost always added too. So, what’s the difference between these two sour-salty solutions?

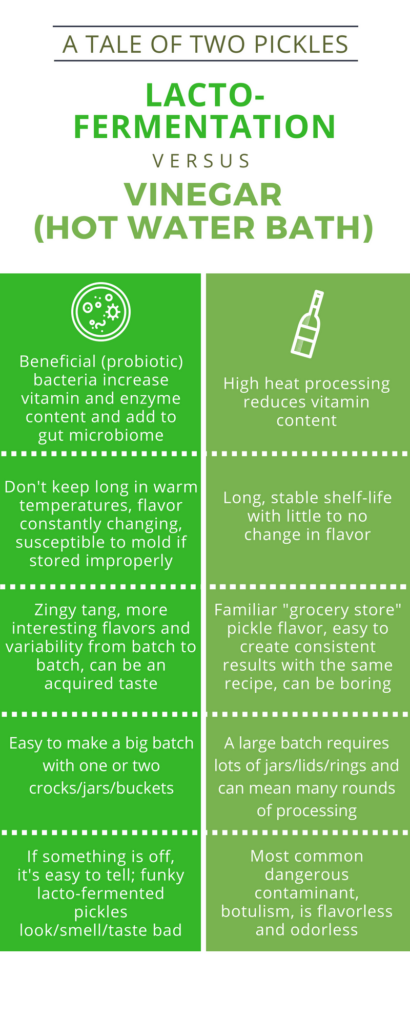

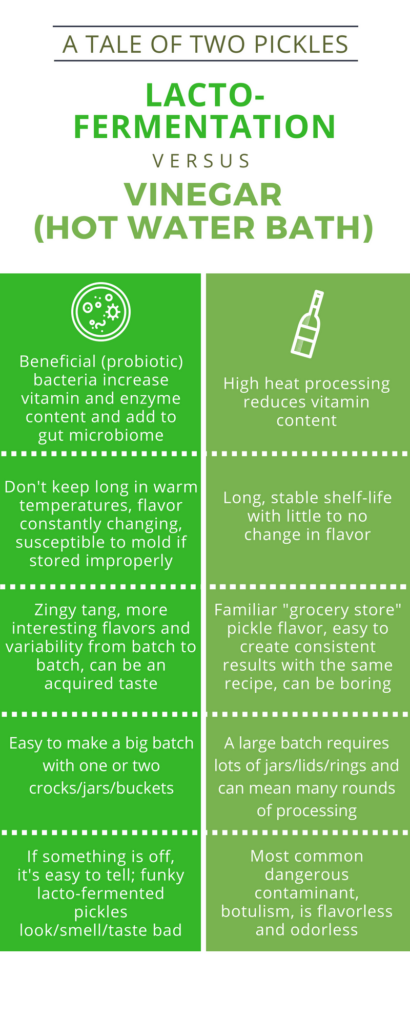

The presence of probiotics, or beneficial bacteria, is the main difference between lacto-fermentation and vinegar pickling. Lacto-fermented pickles are cultured, and full of priobiotics. Additionally, sealing vinegar pickles in a hot water bath is very common. When we do this, we cook both the pickles and the brine. As a result, we can store them at room temperature in their sealed jars for a long time without spoiling. Lacto-fermented pickles are not cooked, and can only be stored for long periods of time at low temperatures (like in a refrigerator or root cellar). Check out our infographic below for a comparison of some of the pros and cons of these two ways to pickle.

Some folks ask: does vinegar prevent fermentation? It does—by lowering the pH so much that bacteria (even good ones) can’t survive. That’s why vinegar pickles don’t contain probiotics unless they’ve been added afterward, which is rare.

Great pickle recipes

Pickle diversity is as vast as human culture. Here are two basic recipes to get started, from two awesome books on food preservation. There are tons of other pickling books out there. We especially encourage you to explore recipes for pickles and preserves from India, Ukraine, Germany and Japan. Those are among the pickle loving cultures who have perfected many piquant delicacies.

Sour Beets (lacto-fermented)

From “Wild Fermentation”

Timeframe: 1 to 4 weeks

Ingredients (for 1/2 gallon):

- 5 pounds beets

- 3 Tablespoons salt

- 1 Tablespoon caraway seeds

Process:

- Grate the beets, coarsely or finely based on your preference

- Sprinkle the grated beets with salt as you go

- Add the caraway seeds and stir to incorporate

- Place the juicy, salt, caraway-y beets into a crock, food-grade plastic bucket, or large glass jar, pack in tightly to squeeze juice from the beets and press out any air bubbles

- Place a weight atop the beets and make sure all of them are submerged

- Cover with a cloth to exclude bugs

- Check after a few days, it will get more sour over time and be “done” in 1-4 weeks depending on temperatures

- When you deem it done, pack into clean jars and store in the refrigerator.

“Dilly” Green Beans (vinegar pickles)

From “Putting Food By”

Ingredients (for 7 pint jars):

- 4 pounds whole green beans

- 1 1/2 crushed, dried red pepper

- 7 fresh dill heads or 3 1/2 teaspoons dried dill seed

- 7 cloves of fresh garlic, peeled

- 5 cups vinegar

- 5 cups water

- 1 cup minus 1 Tablespoon salt (“pickling,” Kosher, or sea salt, not iodized table salt)

Process:

- Sanitize your jars by steaming, boiling, or in a dishwasher

- Fill clean, still-warm jars to the shoulder with clean, trimmed green beans

- In each jar, place 1 dill head or 1/2 tsp dill seed, 1 garlic clove, and 1/4 tsp crushed pepper

- Heat together the water, salt and vinegar to a boil

- Pour brine over the beans, filling each jar 1/2 inch from the top

- Process in a hot water bath canner for 10 minutes after water returns to a simmer

- Remove and let cool, then double-check seals

Learn More Natural Recipes!

The Nourishing Kitchen Retreat

Are Pickled and Fermented the Same Thing?

While pickling and fermenting are often confused, they’re not exactly the same. Pickling is a general method of preserving food in an acidic solution—usually vinegar or brine. Fermentation, on the other hand, is a biological process in which natural bacteria feed on sugars and produce acids that preserve the food.

So, all fermented foods are pickled (they become acidic), but not all pickles are fermented. Vinegar-pickled items skip the fermentation process and are preserved directly in acid, while lacto-fermented foods rely on beneficial bacteria to create that acidity over time.

How to Tell if Pickles Are Fermented

You can usually tell if pickles are fermented by a few signs:

- Cloudy brine: Lacto-fermented pickles often have cloudy liquid due to microbial activity.

- Fizzing or bubbling: You may see bubbles when you open the jar.

- Sour smell: Fermented pickles have a more complex, tangy smell than vinegar pickles.

- Labeling: If it’s store-bought and doesn’t say “raw,” “unpasteurized,” or “fermented,” it’s probably vinegar-based.

Fermented pickles also tend to be stored in the refrigerator, unless they’re canned in a way that stops fermentation.

Can You Ferment with Vinegar?

Short answer: no. Vinegar is too acidic for the beneficial microbes needed in lacto-fermentation to survive. In fact, one of the reasons vinegar is used in pickling is precisely because it halts microbial activity—bad and good alike.

Lactic acid (created during fermentation) develops over time through bacterial action. Vinegar introduces acidity immediately, making it great for shelf-stable preservation, but not for cultivating probiotics. So, if you’re aiming for those live cultures, stick with saltwater brine.

How to Stop the Fermentation Process

To stop fermentation, you need to drastically slow or halt the bacterial activity. Here are some ways to do that:

- Refrigeration: Cooling slows fermentation almost to a halt.

- Move to cold storage: A root cellar or cold pantry can be a good in-between.

- Canning (for vinegar pickles): Boiling and sealing kill microbes and prevent further fermentation.

Once fermentation is stopped, the pickles will stay at their current level of sourness—so make sure to catch them at the stage you like.

Are Pickled Beets Fermented? What About Sauerkraut?

Pickled beets can be either fermented or vinegar-pickled—it depends on the recipe. Traditional recipes like the one from Wild Fermentation are lacto-fermented, while quick pickled beets usually use vinegar.

Sauerkraut, on the other hand, is a classic fermented food. It’s made with only cabbage and salt, and the fermentation process creates its signature tang. If you’re buying sauerkraut at the store and want the probiotic benefits, make sure it’s labeled raw or unpasteurized.

Frequently Asked Questions About Pickling vs Fermentation

Lacto fermentation is a traditional way of preserving food that relies on naturally occurring beneficial bacteria—especially lactobacillus—to convert sugars into lactic acid. When you submerge vegetables in a salty brine (or salt them directly), the salt helps suppress harmful microbes while encouraging the “good” bacteria to thrive. As lactic acid builds, it creates a safe, acidic environment that preserves the food and gives it that signature tangy, complex flavor. This is the same basic process behind classic foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, and many traditional dill pickles.

Unlike vinegar pickling, lacto fermentation is an active living process: the microbes continue working for days (or weeks), changing the flavor and texture over time. Temperature, salt level, and how long you ferment all affect the final result—short ferments are often brighter and crunchier, while longer ferments can become deeper, funkier, and more sour. Because the food isn’t heat-processed, properly fermented foods typically retain live cultures when stored in the fridge. That’s one reason many people include them in their diets for both flavor and gut-friendly microbial diversity.

The main difference is how the acidity is created. Fermented pickles start in a salt brine and become acidic because bacteria produce lactic acid over time. This gradual fermentation develops layered flavors—often garlicky, savory, and pleasantly sour—and can also change the texture in a way many people describe as “alive” or “complex.” If they’re kept raw (not heat processed), fermented pickles can retain live cultures, which is why they’re often associated with probiotic benefits.

Vinegar pickles, on the other hand, are made by adding acidity directly—usually vinegar—so there’s no microbial fermentation required to preserve the food. Many vinegar pickles are heated or canned for shelf stability, which makes them convenient and consistent, but also stops any living microbial activity. Flavor-wise, vinegar pickles tend to taste sharper or more one-note “vinegary,” while fermented pickles often have a rounder tang and more depth. Both are delicious—just different processes with different outcomes.

Homemade pickles can have probiotics, but only if they’re made through lacto fermentation and kept raw. That means you used salt and water (or dry salt) to create a brine, let the pickles sit at room temperature to ferment, and didn’t heat-process them afterward. In that setup, beneficial microbes can remain present in the finished pickles, especially when you store them in the refrigerator to slow fermentation while keeping cultures alive.

If you make homemade pickles using vinegar from the start, or if you can/heat them for shelf stability, you’ll greatly reduce—or completely eliminate—those live cultures. So the “probiotic” question isn’t really about whether they’re homemade; it’s about the method. If your jar is bubbling during the first few days and smells pleasantly tangy (not rotten), that’s often a sign fermentation is happening. For the best chance of retaining live cultures, keep them refrigerated once they taste the way you want.

Most store-bought pickles do not have probiotics, because they’re usually made with vinegar and then pasteurized (or otherwise processed) to make them shelf-stable. Even if a product started with fermentation, heat treatment can kill the live cultures that would otherwise make it probiotic. That’s why shelf-stable pickles in the aisle typically don’t provide the same live-culture benefits as raw fermented foods.

That said, some store-bought pickles do contain live cultures—especially products sold in the refrigerated section that are labeled “fermented,” “raw,” or “unpasteurized.” These are often closer to traditional lacto-fermented pickles and may taste more complex and less sharply vinegary. If probiotics are your goal, the label matters: look for language that indicates fermentation and the absence of pasteurization, and keep them cold to help maintain live cultures. When in doubt, check the ingredients—if vinegar is the main acid and the jar is shelf-stable, it’s probably not a live-culture product.

Yes—adding vinegar at the beginning typically prevents (or severely limits) fermentation because it makes the environment acidic right away. Lacto fermentation depends on beneficial bacteria having a window of time to multiply and convert sugars into lactic acid. When vinegar drops the pH immediately, it creates conditions that discourage those bacteria from establishing a robust fermentation. In other words, vinegar short-circuits the process by doing “instant acidification” instead of letting microbes do it gradually.

That’s why vinegar pickles are considered pickled, not fermented: the preservation comes from the vinegar itself rather than from microbial activity. You can combine techniques in some recipes (for example, adding a small amount of vinegar later for flavor), but if probiotics and traditional fermentation are the goal, vinegar generally works against you. If you want a true ferment, start with salt and water, keep everything submerged, and let time and temperature do the work. If you want a fast, bright pickle with predictable acidity, vinegar is the right tool.

Pickling Resources

If you want to find these items locally, more power to you! If you want to buy them online, we participate in an associate program with Amazon.com, and when you click on the links below, we benefit. Any money that we make from this program goes into a fund that helps us continue to offer free information and resources to everyone.

- Wild Fermentation by Sandor Ellix Katz. All about fermentation, from grain to dairy to vegetables and beyond…not just pickles.

- Putting Food By by Janet Greene, Ruth Hertzberg, and Beatrice Vaughan. The classic guide to food preservation. Focus on vinegar pickling, canning, freezing, etc.

- Fermented Vegetables: Creative Recipes for Fermenting 64 Vegetables & Herbs in Krauts, Kimchis, Brined Pickles, Chutneys, Relishes & Pastes by Christopher and Kristin Shockey. A fun and inspiring recipe book full of delicious ferments.

- Ball Complete Book of Home Preserving: 400 Delicious and Creative Recipes for Today by Judi Kingry and Lauren Devine. From the company that makes a popular brand of canning jars, recipes for vinegar pickles and more.

- 5 Liter Crock with weights, airlock lid, and pounder. This is for putting away large batches of fermented veggies.

- “Easy Fermenter” airlock lids for mason jars. This starter kit includes recipes and a hand pump to exclude oxygen from your pickled as they ferment. Making smaller batches of pickled things in mason jars means you can have more variety, plus you don’t have to scoop your pickles from a large crock into jars for storage, just switch to a normal lid once the pickles are done.

Learn to Pickle Like a Pro

Whether you’re brand new to fermentation or eager to explore more advanced techniques, we invite you to join our in-person healthy cooking classes. Learn from experienced instructors, explore hands-on techniques, and deepen your connection to traditional, nourishing foods.